Radio's Jackie Robinson: Nat D. Williams

Radio's Jackie Robinson: Nat

D. Williams

By DALE PATTERSON

"If Beale

Street could walk, if Beale Street could talk/Married men would pick up their

beds and walk."

-

from "Beale Street Blues", lyrics © W.C. Handy

In the decade of Jackie Robinson, there was yet another man who broke a colour barrier. One year after Robinson became the first black in modern times to play major league baseball, Nat D. Williams became the first African-American in the south to become the regular host of a radio show. It opened the floodgates as many African-Americans would follow him to their rightful place on the airwaves.

Nathanial Dowd Gaston Williams was born October 19, 1907 on famed Beale Street in Memphis; he later dropped the Gaston. A consummate learner, he acquired degrees from several universities including Northwestern and Columbia. His first job, in 1928, was as an editor for the New York State Contender. He began a 21-year writing career with the Memphis World in 1931, before switching to the Memphis Tri-State Defender in 1952. He continued to write until poor health stopped him in the early '70s. His teaching career, at Booker T. Washington, spanned 42 years - from 1930 to 1972.

In addition to all this, Williams was well-known as an emcee at the Palace Theatre, the Memphis equivalent of the Apollo Theatre in New York. It was through his that his skill as an entertainer spread; this and his intimate knowledge of the mid-south's black pool made him a natural choice to become the first black deejay in the south.

Bert Ferguson, who has been called the Branch Rickey of radio, eagerly chose Williams to be his first deejay when he and partner John R. Pepper decided to introduce a black format to their struggling Memphis station, WDIA. Williams just as eagerly accepted the post when signed on for the first time at 4:00 p.m., October 25, 1948, replacing the existing classical music program that had occupied the time slot.

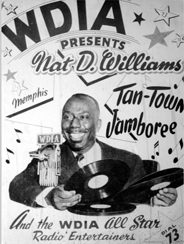

His first record on the show he called Tan-Town Jamboree was Stompin' at the Savoy. He opened this debut show like all the others in the 24 years that would follow: "Well, yes-siree, it's Nat Dee on the Jamboree, coming at thee on seventy-three (on the dial), WDIA. Now, whatchubet." That was followed by a huge, full-bellied laugh and 90 minutes of the best r&b (then called "race" music) around.

Nat D's infectious laugh and strong on-air presence helped him gain an immediate following among Memphis-area blacks and open-minded whites. He also hosted a morning show, Tan Town Coffee Club (6:30-8:00 a.m.) while holding down a teaching post at Booker T. Washington High School (he would return after school for his 4:00-5:30 p.m. shift.) He also teamed with Rufus Thomas on a Saturday show and did a two-hour Sunday program, the Oldtimers Show, which featured older favourites.

But Williams was much more than just a radio man. He wrote for several leading newspapers, edited the school paper, taught Sunday school, sang in the church choir (he never missed a session in 40 years), led a Boy Scout troop and co-ordinated the annual Tri-State fair. He also found time for his wife and two kids and his students; at one time he had more of his students in state legislatures across the U.S. than any other black teacher. Said one fellow teacher "Children strove to go into his classroom."

Williams did not see the decision to put him on the air as a crusading one - he saw it quite rightly as business decision. While acknowledging Ferguson and Pepper as progressive, he noted that they were like any businessmen out to make money. For his part, he saw the move as another chance for black Americans to unlock their economic and political promise.

In time, other black deejays would follow Nat D. to WDIA, among them A.C. Williams, Martha Jean "The Queen" Steinberg, Rufus Thomas and B.B. King. And around the country, African-American radio stars such as Jocko Henderson and Jack "The Rapper" Gibson started to emerge. But Nat D. was the first, and like Jackie Robinson had to overcome considerable white skepticism and resistance (yes, there was hate mail and phone calls) in his early years.

Nat D. held down his afternoon show - never missing a shift - until he retired from the air following a stroke in 1972. He had high ratings right up to the end. The man who hired him, Bert Ferguson, left the station in 1970. Williams died October 27, 1983 in his hometown of Memphis, eight days after his 77th birthday.

As he lay on his deathbed years later, his body and mind wasted by the last of four strokes, his daughter Natoyen said Williams still remembered the tune to "Beale Street Blues." The years at WDIA obviously meant a great deal to him, just as his presence there was valued by others. Somehow, it seems that we owe the greater debt.

(Much of the information for this profile was found in the excellent book, "Wheelin' On Beale", by Louis Cantor (c) 1992, Pharos Books.)

RETURN TO ROCK RADIO SCRAPBOOK